Schrodinger’s Ptarmigan, exposed.

Journal Entry Jan 29, 2014

People think of this landscape as barren but it’s not. Harsh, yes. Forbidding, yes. But barren? The whole land is alive; when we pass through it clumps of snow detach themselves and streak across the crust as snowshoe hares, or transform into the soft flurried panic of ptarmigan in flight. As evening falls we hear the ptarmigan chuckling from the buckbrush, muttering in their goblin voices, “go-back, go-back”, but when we look for them we find only shadows.

Because every odd white blob is equally likely to be either a creature or a piece of snow, I often think that until we touch them, they are both.

Marlen misses the wooded valleys of his family’s trapline, and we were both relieved when we turned a corner and could see the first trees down and ahead, but…mountain passes will always be sacred places to me, I think.

Coming down from the pass to the first of the trees.

That said, this day has been anything but easy

.………………..

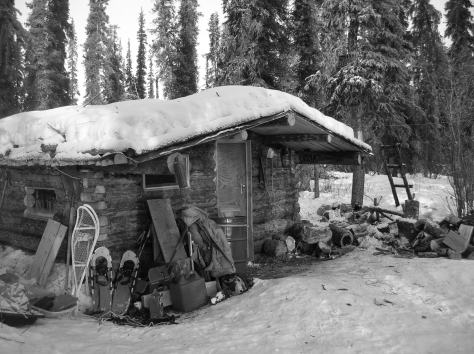

Have you heard the old joke about the trapper who had to shoot his bush partner?

We made it to Wrong Turn Creek on the night of the 29th, much later than we expected. We’d both been thinking of arriving as the end of the day, but of course we still had to make camp. By the time we had the trees cut and limbed for the walltent frame it was dark. By the time we actually got to bed the moon was high, high over us and we were too tired to care that the spruce boughs we’d put down were unevenly spaced, and that the tiny box stove smoked appallingly.

Morning in the spruce tree forest.

Our cozy home away from home

We spent the 30th relaxing (there was some gorgeous overflow ice on the creek and we went sliding) and making the walltent livable. That night we heard wolves in the next valley. I went outside and howled back and forth with them, as Cleo pressed herself nervously against my leg.

On the 31st we crossed the pass again.

So anyway. This joke.

This fellow comes to town, scruffy and thin and wild about the eyes, and very much alone. His friends and family, they ask him how his winter went, and he shakes his head.

“Terrible, terrible.”

“What happened?”

“Oh,” he says (and you have to say this bit in an earnest and mournful voice, for the joke to work) “I had to shoot Billy. He went crazy. Put the little frying pan on the big frying pan hook!”

I’m not going to shoot Marlen. He’s my oldest, dearest friend. I’m not going to shoot him.

We’re crouched behind a tiny clump of black spruce, high on the pass just east of my family’s first cabin.

It’s dark. The moon is just a sliver in the sky, although you can see the suggestion of its full circle. “The new moon holds the old moon in its arms,” someone used to say about that. The stars are out, and the wind is hungry, catching at our loose ends like it wants to unravel us.

We’ve stopped for five minutes to drink the last of the lukewarm tea from our thermos, gnaw at the frozen hunk of dates that’s serving as today’s trail mix, and steel ourselves for the final push to the cabin.

And we’re fighting about grammar.

“It’s not important,” I’m saying. “I mean, it’s just a double-negative. I don’t really care. But you are wrong.”

Marlen nods. “Right,” he says. “Right, right. I see what you mean, generally, but isn’t this the exception?”

Clutched in my numb and mittened hands, the tea is getting cold. The trail is not getting shorter. The wind is not getting kinder. I clutch my snowshoe, unsure whether I want to run Marlen through with the tail end of it, or start diagramming sentences in the snow.

“I had to shoot Billy,” I say.

Marlen grins. “He couldn’t not keep his double-negatives straight!”

Probably I’m not going to shoot him.

During a long day of breaking trail. Marlen, bless his soul (and his long legs) went first most of the time.

…………………….

Journal Entry – February 1, 2014

Back at the West Hart. We came all the way from Wrong Turn yesterday, and it took us about nine hours.

The sky was perfectly dark when we got to That Bloody Hill. Going up it was impossible to tell how far we’d come, or how far we had to go. I could only (barely) see the ground in front of me, and some vague movement over my shoulder where Marlen was. Since there was no end in sight I wasn’t as aware of time passing – the moment I was in felt infinite. There was nothing in the world but the wind and the stars and the next step. And the next.

And then we were up, and the wind was terrible. Marlen put his headlamp on and we both sat on our sleds and aimed them into the darkness. It was the eeriest thing. All I could see was the thin light from his lamp, disappearing down into the valley ahead of me. I was braking constantly with my feet, but the crust was so slick that I was out of control half the time. Every so often a tree would loom up and swoop past, perilously close, or the hill would tip suddenly steeply downward. There wasn’t any wind on that side of the Hill, so everything was quiet except our breathing and occasional shouts. Sometimes the crust would vanish and we’d find ourselves floundering in deep snow, or pitched forward into clumps of willow. It was scary, but it felt so out-of-my-hands that there was no point really worrying.

It was absolutely the most fun I’ve ever had on That Hill.

And, obviously, we survived.